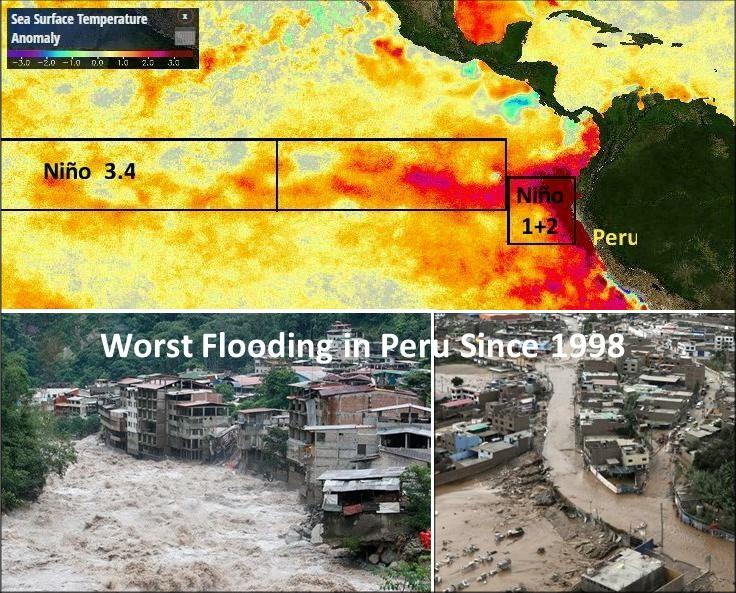

The worst flooding in 20 years is scouring the arid landscape of coastal Peru. Exceptionally warm water in the Pacific Ocean is fueling torrential rain in western South America, which then comes pouring down out of the mountains. The extraordinary amount of water has overwhelmed surrounding towns.

It looks a whole lot like El Niño in Peru, but you won’t be hearing that description from climate forecasters anytime soon.

Flooding is expected to continue for another two weeks, and the death toll is a moving target. However, 72 people have died so far as of Saturday, according to the Associated Press. In the capital city of Lima — an arid region that rarely sees rain let alone deadly flooding — authorities pulled people from the muddy water.

On March 10, Climate.gov’s Tom DiLiberto said rainfall in this region is running 10 times that of normal:

With more than a month left to the season, 2017 is already likely one of the wettest years on record for San Miguel in the Piura province. Around 10 inches of rain has fallen since January 1, when, on average, the entire rainy season usually totals just two inches of rain. Farther inland in the Piura region, a weather station in Morropón recorded 43 inches of rain since the start of 2017. At this point of the year — early March — Morropón’s average rainfall is about 4 inches.

The warm ocean water behind this month’s flooding suggests another El Niño may be forming. The water is so warm, actually, that Peru climatologists declared a “coastal El Niño” to communicate to the public the kind of conditions they should expect and prepare for.

The situation doesn’t meet NOAA’s technical definition of an El Niño, so you won’t be seeing the agency declare its arrival — perhaps for months — but meteorologists can’t ignore this technically unnamed phenomenon’s devastating impact.

NOAA says the ocean is still in a neutral condition — meaning neither El Niño or La Niña — but forecast models used by the Australian Bureau of Meteorology suggest El Niño might arrive as early as April.

It’s a tough call to make, though, since the region is known to have a “spring barrier” on forecasts. For whatever reason, El Niño forecasts made in spring tend not to perform that well.

But the warm water is blatantly obvious off the coast of South America in 2017. It’s kind of like half an El Niño, but for all intents and purposes in Peru, it might as well be a whole one. Peru’s president said late last week that the flooding is the worst for the country since one of the strongest El Niño years on record.

“There hasn’t been an incident of this strength along the coast of Peru since 1998,” President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski said in a statement Friday.

Nearly 400 people died that year in floods.

Categories: Flood